Adopt-a-Book

An Initiative of the Friends of the University of Adelaide Library

Memoir of Mrs. Barbauld, including letters and notices of her family and friends

Anna Letitia Le Breton (1808-1886)

London: George Bell and Sons, 1874

Rare Books & Special Collections

Rare Books Collection RB 92 B23

We thank our donor...

Conservation treatment of Memoir of Mrs. Barbauld... was generously funded by Adopt-a-Book donor, Paul Wilkins. His valued contribution has ensured this important 19th century narrative and collection of poetry will be available for future generations of researchers for many years to come.

Synopsis

Anna Laetitia Barbauld was born at Kibworth Harcourt in Leicestershire in 1743. Her father, John Aikin, was minister of a nearby Presbyterian church and headmaster of the Dissenting Kibworth Academy. Her mother, Jane Jennings Aiken, also a Presbyterian Dissenter, provided Anna with a conventional domestic education, though Anna later convinced her father to teach her languages such as Latin and Greek and other subjects considered inappropriate for women at the time. This desire for education, proved worrisome for Anna’s mother. She strongly believed her daughter would remain a spinster as a result of her intellectualism and, consequently, the two never shared a bond such as that which existed between Anna and her father. Indeed, Anna received multiple offers of marriage during her youth, and she turned them all down until 1774.

In 1771 the first of Barbauld’s poems was published in her brother’s book, John Aikin’s Essays on song-writing. Two years later, she produced her own major collection, simply titled Poems. Revealing her affection for family and friends, her religious and political beliefs and her thoughts about what it meant to be a woman and a poet, the book was enormously successful and Barbauld became one of England’s most respected literary figures almost overnight.[1] In the midst of its success, Anna accepted Rochemont Barbauld’s offer of marriage, and the pair moved to Suffolk where Rochemont had been offered a congregation and a school for boys.[2] In 1775, barely a year into their marriage, Anna, likely concerned that she and her husband were not to have children, wrote to her brother asking him whether they might adopt one of his. It was agreed upon and the third son, Charles, was raised as their own. He would later become a source of inspiration for two of Barbauld’s most successful books - Lessons for Children (1778-9), a four-volume set of stories, written in conversation style, about natural history and Hymns in Prose for Children (1781), a devotional work not to be sung in church but memorised instead and recited aloud.[3]

Towards the latter part of the 18th century Barbauld’s writing assumed a more political focus, and during the French Revolution she published a piece which may have instigated the beginning of her fall from favour. An Address to the Opposers of the Repeal of the Corporation and Test Acts (1790) was a “highly charged pamphlet written in biting and satirical tone” which argued that Dissenters deserved to enjoy the same civil rights as any other men.[4] Most readers simply couldn’t believe it was written by a women; they were shocked by it, though probably not as much as they were by her next piece. After another of William Wilberforce’s efforts to suppress the slave trade failed to pass Parliament, Barbauld produced her Epistle to William Wilberforce on the Rejection of the Bill for Abolishing the Slade Trade (1791). It essentially called Britain to account for the sin of slavery and condemned the avarice of a country content to prosper through the labour of enslaved human beings.[5] She stirred the political pot further in 1793 when she published Sins of Government, sins of the Nation. The sermon was written at a time when the Government had called on the nation to fast in honour of the war. For Dissenters, this meant violating their conscience by praying for success in a war they disapproved of; it didn’t sit well with Anna, and her essay attempted to determine what the proper role of the individual actually was in the state – insubordination could certainly undermine a Government, she wrote, but there were some lines of conscience that one simply could not cross in obeying a government.[6]

In 1802 Anna and her husband moved to Stoke Newington, where the latter assumed responsibility for the pastoral duties of the Newington Green Chapel. Rochemont’s mental health had begun to fail and he became increasingly violent towards his wife. Sadly, in 1808, he snapped altogether, grabbing a knife from the dinner table and chasing Anna around the room with it; her only option for escape was to leap out of the window into the garden.[7] Later, that same year, Rochemont drowned himself in the New River, leaving Anna devastated. She wrote of her grief and loss in the poem, Dirge.[8]

In 1812 Barbauld produced what would be her final poem, Eighteen hundred and eleven[9]. It was shockingly radical and delivered the final blow to her reputation, damaging it irreparably during her lifetime. At the time of publication, Britain had been at war with France for a decade and was on the verge of losing the Napoleonic Wars. Her poem criticised the war and suggested that England was waning, whilst America was waxing, and to the latter all of Britain’s wealth and fame would go; Britain would essentially become nothing but an empty ruin.[10] Her negativity was not well received. Reviews of her piece were, at best, cautious but many were patronizingly negative, some were outrageously abusive.[11] Barbauld was stunned by the reaction and, although she continued to write, never published again. She passed away in 1825 and was buried in the family vault in Saint Mary’s, Stoke Newington.

After Barbauld’s death, her niece, Lucy Aikin, published two collections of Anna’s works: The works of Anna Laetitia Barbauld, with a Memoir by Lucy Aikin (1825) and A Legacy for Young Ladies (1826). She selected the material from Barbauld’s manuscripts which, sadly, were later lost in the 1940 bombing of London. In 1874 her great niece, Anna Letitia Le Breton, produced her Memoir of Mrs. Barbauld, including letters and notices of her family and friends, to which she added a few additional works. In its preface, Letitia described how she was “Earnestly desiring to revive some memory of one who though enjoying in her lifetime a considerable amount of literary fame, is now, from the circumstances of her works having been long out of print and difficult to procure, comparatively unknown to the present generation…”. She wanted to provide a fuller account of Barbauld’s life that Lucy Aikin had been unable to, musing “Feelings of delicacy towards members of Mr. Barbauld’s family, then living, prevented the true account being given of the unfortunate state of mind with which her husband became afflicted, a calamity which in a great degree crippled her powers for many of the best years of her life.” The Memoir included letters to Anna from her mother, from her dear friend Joseph Priestley and from Maria Edgeworth, as well as those from Anna to her brother, amongst others. Towards the back of the book, readers could find Barbauld’s epitaph and in the Appendix, a number of her poems, including the hauntingly beautiful Life,[12] as well as her essay Against Inconsistency in Our Expectations.

Barbauld’s legacy of prose is noteworthy. Though she disappeared from the literary landscape for much of the 18th and 19th centuries, due in part to the influence of poets such as Coleridge and Wordsworth, who turned against her in their later, conservative years, Barbauld’s contribution to educational and political writing, as well as literary Romanticism, remains significant. She was the first to really consider the needs of the child reader, demanding her books be printed in large type and developing an informal “dialogue” style of writing between parent and child. She exposed children to subjects such as botany, zoology and numbers and inspired others to write at a high standard for the young. Her poetry and political essays reflected an independence of thought astonishing for its time and she proved a remarkable model for contemporary women writers to emulate.

Today, through the rise of feminist scholarship, Anna Barbauld is deservedly remembered as much more than a moralizing children’s author; she has proven to be one of Britain’s most vibrant voices - a poet, essayist, literary critic and editor who wrote with a strength of conviction and who enjoyed enormous success at time when women were rarely professional writers.

Original Condition

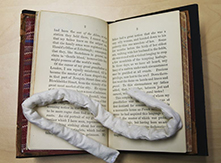

Half-bound in sheepskin with cloth sidings. Extensive Sellotape repair to spine with two paper call number labels also taped to spine and cover. Multiple splits to textblock, revealing sewing system and spine lining. Front and rear boards detached entirely from textblock. Head and tail of spine showing signs of wear and board corners beginning to separate, with leather covering lifting away. Requires rebacking and re-sewing.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Restoration by Anthony Zammit

Solvent applied to Sellotape to carefully remove it from spine and from both front and back covers, and call number labels discarded. Textblock resewn. Card lining removed from original sheepskin spine and a new spine constructed from calfskin. New card lining applied to the back of the textblock and the new calf leather inserted underneath the existing leather on the front and back covers, essentially rebacking the book. Original, saved spine leather (with its gilt titling) reapplied to the new spine. Hinges reinforced with cloth sympathetic in colour to the endpapers, and front and rear endpapers readhered to cloth hinge. Board corners consolidated with PVA and new calfskin applied over the corners.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Footnotes:

[1] "Anna Laetitia Barbauld." New World Encyclopedia, 23 Mar 2016, accessed 7 August 2018 http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/p/index.php?title=Anna_Laetitia_Barbauld&oldid=994851.

[2] "Anna Laetitia Barbauld." New World Encyclopedia, 23 Mar 2016, accessed 7 August 2018 http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/p/index.php?title=Anna_Laetitia_Barbauld&oldid=994851.

[3] “Hymns in prose for children”, British Library, undated, accessed 7 August 2018,

https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/hymns-in-prose-for-children

[4] "Anna Laetitia Barbauld." New World Encyclopedia, 23 Mar 2016, accessed 7 August 2018 http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/p/index.php?title=Anna_Laetitia_Barbauld&oldid=994851.

[5] "Anna Laetitia Barbauld." New World Encyclopedia, 23 Mar 2016, accessed 7 August 2018 http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/p/index.php?title=Anna_Laetitia_Barbauld&oldid=994851.

[6] "Anna Laetitia Barbauld." New World Encyclopedia, 23 Mar 2016, accessed 7 August 2018 http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/p/index.php?title=Anna_Laetitia_Barbauld&oldid=994851

[7] “Anna Laetitia Aikin Barbauld (1743-1825)”, University of Pennsylvania, undated, accessed 7 August 2018,

http://digital.library.upenn.edu/women/barbauld/biography.html

[8] Barbauld, Anna Laetitia, Dirge, 1808, accessed 8 August 2018 via University of Pennsylvania, http://digital.library.upenn.edu/women/barbauld/works/bal-dirge.html

[9] Barbauld, Anna Laeitia, Eighteen hundred and eleven, accessed 8 August via University of Pennsylvania, http://digital.library.upenn.edu/women/barbauld/1811/1811.html

[10] "Anna Laetitia Barbauld." New World Encyclopedia, 23 Mar 2016, accessed 7 August 2018 http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/p/index.php?title=Anna_Laetitia_Barbauld&oldid=994851

[11] "Anna Laetitia Barbauld." New World Encyclopedia, 23 Mar 2016, accessed 7 August 2018 http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/p/index.php?title=Anna_Laetitia_Barbauld&oldid=994851

[12] Barbauld, Anna Laetitia, Life, Memoir of Mrs. Barbauld, London: George Bell and Sons, 1874, accessed online 8 August 2018 via Poetry Foundation, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/50602/life-56d22dcfeee28

Lee Hayes

August 2018