Adopt-a-Book

An Initiative of the Friends of the University of Adelaide Library

The history of the Royal-Society of London, for the improving of natural knowledge

Thomas Sprat (1635-1713)

London: Printed by T.R. for J. Martyn... and J. Allestry, 1667

Rare Books & Special Collections

Strong Room Collection SR 509 S76

We thank our donor...

Conservation treatment of The history of the Royal-Society of London... was generously funded by Adopt-a-book donor, Barbara Kidman. Her valued contribution has ensured this 17th century book on the history and purpose of one of Britain's oldest societies will be available for future generations of researchers for many years to come.

Synopsis

Divided into three parts, The history of the Royal-Society of London documents the state of natural knowledge prior to the Society’s establishment; the founding of the Society, and the value of the knowledge sought by the Society. It is not so much a full and accurate history of the Society, rather a written defence of its activities and objectives.

The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, or “Royal Society”, as it is commonly known, began unofficially in 1660, when a group of natural philosophers announced the formation of a “College for the promoting of Physico-Mathematical Experimental Learning”. The group initially consisted of twelve and included, amongst others, mathematician and distinguished architect Christopher Wren; Irish philosopher, chemist and physicist Robert Boyle; philosopher and clergyman John Wilkins; Scottish diplomat, judge and natural philosopher Robert Moray, and mathematician William Brouncker.

The Society members were influenced by Francis Bacon and the new techniques he promoted for investigating phenomena and acquiring knowledge. They met weekly to discuss a wide range of scientific topics, and conducted experiments to expand their knowledge of water, air and fire, as well as light, sound, colour, gravity, motion and the growth of plants. King Charles II took a great interest in the Society’s activities and was present at some of its earliest experiments. His approval saw the issue of a Royal Charter in 1662 which created the “Royal Society of London”. A second Royal Charter, issued the following year, would name the organisation “The Royal Society for London for Improving Natural Knowledge”.

Spurred on by the Royal Charter, the Society began to publish. The first book it produced was John Evelyn’s 1664 Sylva, or A discourse of forest-trees and propagation of timber in His Majesties dominions. This was followed a year later with Robert Hooke’s Micrographia, or Some physiological descriptions of minute bodies made by magnifying glasses… 1665 also saw the publication of the first issue of Philosophical Transactions, edited by the Society’s secretary, Henry Oldenburg, at his own expense. Its publication was later assumed by the Society and today it remains the oldest scientific journal in continuous publication.

Despite this success, the Society was concerned about negative publicity. Its fellows were vulnerable to suspicion given their pursuit of new knowledge and they risked accusations of atheism at a time when monarchies throughout England, Scotland and Ireland were being restored. To placate any critics, the Society decided to publish an apologia of sorts. They commissioned Thomas Sprat, churchman and protégé of Society Fellow John Wilkins, to document the history and intentions of the Society. The history of the Royal-Society of London was published in 1667. It discussed the acquisition of knowledge by the ancient priests, the Greek philosophers, the Romans and the scholastics of the medieval universities. Chymists and alchemists also received a mention but it was the Society’s guiding principles which drew most of Sprat’s attention. Highlighted were the notions that men of all nations and religions were welcome in the Society, and that it should be a central repository for written information – the first of its kind. [1]

References to Francis Bacon are scattered throughout the book. In fact, Sprat’s underlying message is that there is much to be gained from observation and experiment, as opposed to beliefs in preconceived theories. He concludes the book with a rebuttal of criticisms of the Society, pointing out the beneficial impact of experimental philosophy on industry and trade. Adding weight to the message is the book's carefully considered frontispiece, designed by John Evelyn and etched by the renowned Czech, Wenceslas Hollar. It depicts a bust of Charles II, flanked on one side by the Society’s first President, William Brouncker, and on the other by Francis Bacon, the pioneer of scientific method.

Original Condition

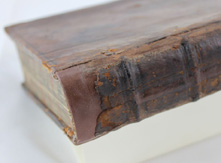

Deteriorating calf skin with sections of leather missing entirely from head and tail of spine and from front and rear board corners and edges. Front board detached and rear board starting. Board corners separating and in need of consolidation. Headband loose and supporting thread unravelling from textblock. Large section of frontispiece paper missing and textblock split in multiple places. Requires rebacking and re-sewing.

|

|

|

|

Restoration by Anthony Zammit

New custom-dyed leather applied to head and tail caps and to the centre of the spine where much of the original was missing. Splitting board corners and edges consolidated and re-covered with calf skin. Textblock re-sewn and headbands re-attached. Missing paper from frontispiece infilled with Japanese repair paper. Inside front and rear joints also strengthened and covered with Japanese Kozo paper.

|

|

|

|

|

Footnotes:

[1] Hopkinson, Ian, Book review: The history of the Royal Society of London by Thomas Sprat, 2010 http://www.ianhopkinson.org.uk/2010/10/book-review-the-history-of-the-royal-society-of-london-by-thomas-sprat/