No laughing matter: how we can learn from comics

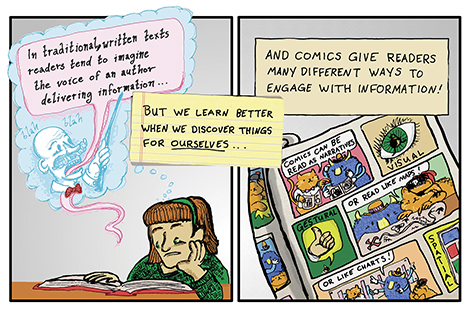

Illustration: Aaron HumphreyYou can’t use Spider-Man to teach complex academic disciplines, says PhD student Aaron Humphrey. For a start, there is no point in drawing a traditional lecturer, even one with super powers, delivering a traditional lecture.

But you can use the format of comics in training and education. In fact people have been doing just that for 70 years, and our social media revolution, where text and images integrate on screen, all but ensures a golden age of comics in education.

Mr Humphrey, an American-born South Australian came to comics from film school, a reversal of the more regular route, after doing the prestigious screenwriting degree at Chapman University in Orange County, California. “I liked the way the reader has more control in a comic book than of a film. You consume film privately, in cinemas at least, and talk about them after but with comics you talk as you read and everybody constructs comics differently.”

Mr Humphrey makes his case by practising what he preaches in his doctoral research on using comics in education. He reworked a chapter of his thesis from 65 pages of 15,000 words into a 22-page comic, which is one of two comics-style articles by Humphrey scheduled to be published in academic journals later this year. “Increasingly, serious journals are presenting original research as comics – it allows access to different modes of presenting and thinking about information,” he says.

Comics are also used widely in medicine to educate patients or help doctors understand patient experiences. The growing ‘Graphic Medicine’ movement includes a conference, last held at Johns Hopkins University, where Mr Humphrey gave a presentation about a comic he was commissioned to create by Mackay Base Hospital in Queensland, which is being used to help new doctors deal with stress.

“People are not as sceptical as you might think. I am always hearing examples of comics in education. And we are moving to image-based communications in daily life, on our phones and the internet. Much of our literacy is now visual.”

“Comics are also congruent with the way people express themselves,” Mr Humphrey adds. This explains why the Mackay Base Hospital comic worked – a survey of the interns who received it showed them feeling better prepared for the emotional challenges of hospital life than previous cohorts who were given conventional texts.

While education comics might seem a contemporary creation of our image-rich, text-light, screen-focused Facebook age; Mr Humphrey says they are older than Spider-Man. A founder of the graphic novel genre, Will Eisner (and creator of “masked crime-fighter”, The Spirit), started an education comic, Preventative Maintenance Monthly, for the United States Army in 1951, which still runs today.

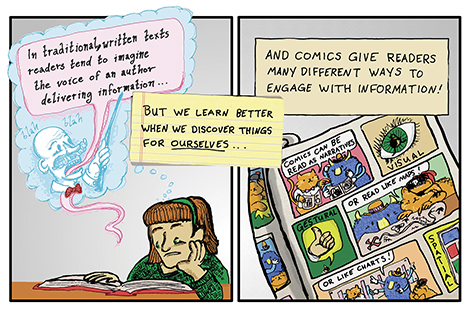

It’s easy to understand why these graphic training manuals work; the comic format breaks down complex information into images and text, which readers can pour-over until they get it. But the format also works with abstract ideas – which Mexican artist Eduardo del Rio, better known as Ruis, realised with his genre-creating primer, Marx for Beginners. Ruis created a learning environment “where abstract ideas and theories can be observed, experienced, and reflected upon in order to construct knowledge,” Mr Humphrey says.

Mr Humphrey says comics are inspiring because, “they give us a way of showing what we mean rather than just telling it. They give us tools to do different things in regard to the functions of language.”

If anybody thinks images just over-simplify ideasand information that is better conveyed by spoken or read text, Mr Humphrey suggests they look at a map: “You could not write a map out as text, it would be far too complex.”

As for anybody who assumes comics are easier to produce than traditional textbooks or lectures they should try it. “Writing takes a style of language, when you break it apart for a comic you are not just changing the presentation you have to re-think the process.”

For lecturers who know how to use the form, comics are especially suited to undergraduate teaching.

“They make you think more about what you are saying, they don’t suffer from the elliptical nature of academic writing, they have a way of cutting through extraneous stuff and getting across hard ideas.”

Comics are also terrific teaching tools. The format is super-suited for presenting complex information – charts, diagrams and texts are all easily combined in a comic format, which is especially useful for slides in lecture presentations.

So what disciplines would he like to see a textbook or course notes in a comic format? Mr Humphrey says he would like to write a comic book for his own field of media theory and that many fields, from maths to epistemology, would suit the format.

Which raises the inevitable question, while he can write academic comics, can he draw? “I am not fantastic, but I can express myself as a cartoonist,” he says.

Not to worry, it’s the ability to teach by integrating image and text that is the big picture when it comes to university comics.

|

|

Media Contact:

Media Office

Email: media@adelaide.edu.au

Website: http://www.adelaide.edu.au/news/

External Relations

The University of Adelaide

Business: +61 8 8313 0814

For more news on the research and educational achievements of the University & our alumni read the University's bi-annual magazine, Lumen.

|

|