Ern Malley and the Angry Penguins

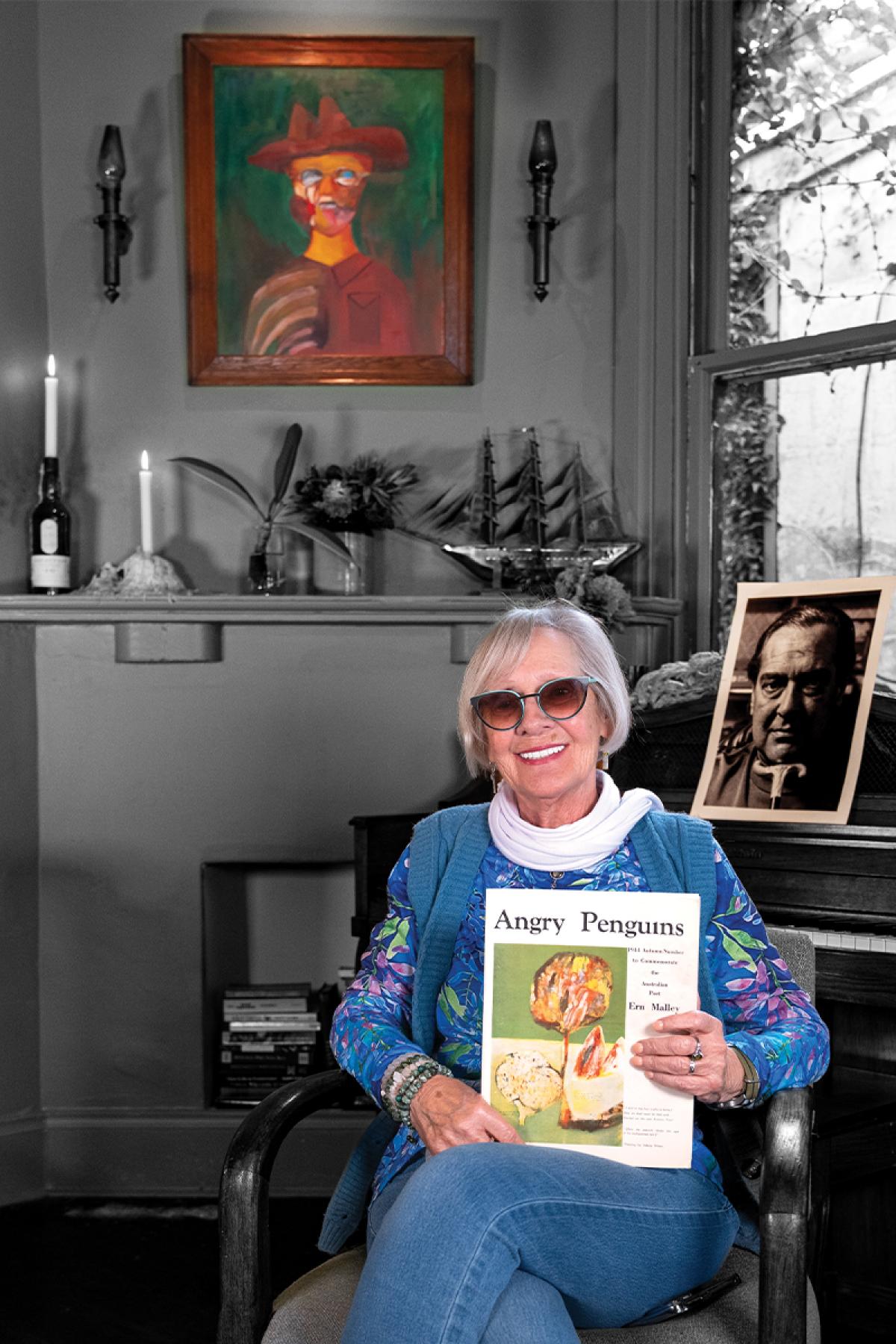

Taken at the Ern Malley Bar, Magill Road, Stepney, Samela Harris is holding a copy of the original Angry Penguins magazine, a reproduction of a Sidney Nolan painting of Ern Malley, and a photograph of Max Harris resting his chin on one of his signature canes and looking over his daughter’s shoulder.

There was something strange about that handsome old sideboard. Years rolled by, but its bottom doors were never opened. It was decidedly odd. I don’t remember anything being said, but I knew I was not supposed to open them.

One day, however, as an only child alone in the house and at a loose end, I dared to peek inside. It wasn’t hard. The doors were not locked. The contents did not look particularly exciting. Just a scrapbook and some yellowing newspaper clippings. But, oh what glaring black headlines.

“Obscenity in advertising law…”And someone called Ern Malley. Unwittingly, I had unearthed the record of a massive tabloid scandal with my dad in the middle of it all. I was maybe seven on the day that I opened the cupboard. I had never knowingly heard the name “Ern Malley”. It was to follow me for the rest of my life.

My father was a poet called Max Harris. He and Mary Martin ran what was to become a wonderful, arty Adelaide bookshop empire together. They had been best friends since their time at the University of Adelaide when it was reputed that Mary steered him around the campus so he could keep focused on his voracious reading. Max, studying economics, was a gifted student, a literary prodigy, a precocious young intellectual.

The 1930s and ‘40s were fertile years for students at Adelaide Uni. Creativity was in ferment. A group including Max had produced the daring Phoenix literary magazine, which was to become Angry Penguins magazine, even more wildly avant-garde and cutting the modernist cultural edge of those excitable early wartime years.

And the old school didn’t like them. Not one bit. They hated them. Bad poetry, they said. One old traditional poet called A. D. Hope became a secret ringleader of the opposition, inspiring a couple of young poets serving military duty to ape the abstract lyricism of the new modernist poetry and create hoax poems by a faux poet.

They called him Ern Malley, assembled diverse lines from random books, styled them to resemble the new wave of verse, then submitted them to Max and his Angry Penguins magazine. With the poems came a letter purporting to be from Ern Malley’s sister, Ethel, who wrote that they had been found after her brother’s death, and asking if they were worth publishing.

Max suppressed initial suspicion because he really loved the poems. He and his team, which included the artist Sidney Nolan, not only published the poems but made a fuss of their purportedly deceased creator. A painting by Nolan adorned the cover and he later went on to create a series of “portraits” of Ern Malley.

Ern Malley was a hit. Then the hoaxers bragged to the media that it was all a prank to show up modern poetry which, clearly, they had found hard to understand.

And, suddenly, of all madly unlikely things, the police were interested in poetry. They’d been tipped off that some of the lines contained sexual innuendo.

This was a time of censorial conservatism. The police took Max to court as the publisher.

The media went wild, and poetry was now in the headlines. Max was grilled mercilessly by police and prosecuted. He had to explain and justify almost every line of the poems. He had to defend the very soul of poetry. He was just 22.

The glorious irony of it all was that those hoaxers accidentally wrote the best poetry of their lives. Few remember their names, but Ern Malley lives on.

As it was for my father, my identity became intertwined with Ern’s. I carry the troublesome seed of the hoax’s creative impetus. ‘Please explain,’ asks the world. ‘Ok,’ say I. ‘Here’s the story.’ It’s as if he’s become part of my DNA.

I did not inherit my father's creative originality, however. Still in his teens, Max already had written a pioneering surrealist novel and had poems published in all directions. Not I.

My years at Adelaide Uni were rich with lively political clubs, debates, Footlights' satirical revues, student unionism, protest marches, and Prosh rags. These were happy days, stimulating busy days, amid fabulous fellow students: academics, activists, artists, satirists, composers, and burgeoning politicians. The “we can change the world” broad educational life that universities used to be all about.

I was never struck in the brain by that poetic impulse I had witnessed in action on my father. However, I was, am and ever will be a writer.

In 1964 I entered the University of Adelaide as a law student. It was an interesting time. This was the tail end of the Menzies era in Australia and the end of the epic rule of Sir Tom Playford as Premier. The 1965 election of Frank Walsh was to produce the first State Labor government in 32 years.

The lawyers I had known were poets and artists and, while I blithely envisaged a career path in an Adelaide law firm, I had not anticipated the rigours of rote learning and the inflexibility of the subjects ahead of me. I soon became a rebel student, arguing points of law which, of course, I could not change.

Then, John Bannon (LLB 1967, BA 1968, Doctor of the University honoris causa 2014), an older law student active in the Student Representative Council (SRC), suggested I edit On Dit. He nominated me and I was duly elected alongside Piers Plumridge (LLB 1969) and John Waters (LLB 1967).

We were a diverse and colourful trio. There were lots of editorial disputes between the politically feisty Waters and the arty-farty me. Gentle Piers disapproved of our raucous debates and resigned spectacularly very early on – throwing his vintage typewriter down the hall outside the On Dit office.

This was a lively period at the University. The SRC was a powerful, well respected, and supportive backbone for the student body. Some of its leading lights went on to become leading political figures, notably John Bannon, who became Premier, and Chris Sumner (LLB 1966, BA 1968), who became Attorney General.

Student activism was taken for granted and various causes brought students out en masse into the streets. Most memorable was the protest against the death sentence and what was to be the last hanging in South Australia, the case of Glen Valance.

Of my own special assignments, Bob Dylan’s first visit was the most exciting. It was my first superstar press conference. Editing On Dit led to a career in journalism and I abandoned law as a lost cause.

I was lured from Law School to The News on the Murdoch Scholarship of the day, and went on to work for The Australian; AAP/Reuters in Fleet Street, London; The Evening News in Edinburgh; and then The Advertiser back in Adelaide. I was the first woman on two

general news floors, the country’s first female Australian Rules Football writer in the 1960s, and in the early naughties I was The Advertiser’s inaugural online editor and founding chair of the Adelaide Critics Circle.

All thanks to my father, the University, On Dit, and the poet who never was, but who lives on in me still, Ern Malley.

Samela Harris is an Australian journalist, critic, columnist, author, and blogger. Her career as an arts journalist and cultural commentator spans a variety of print media. In 2017, for these and other contributions to South Australian cultural and public life, she was awarded the SA Media Lifetime Achievement Award and inducted into the SA Journalists’ Hall of Fame.