Rare Books

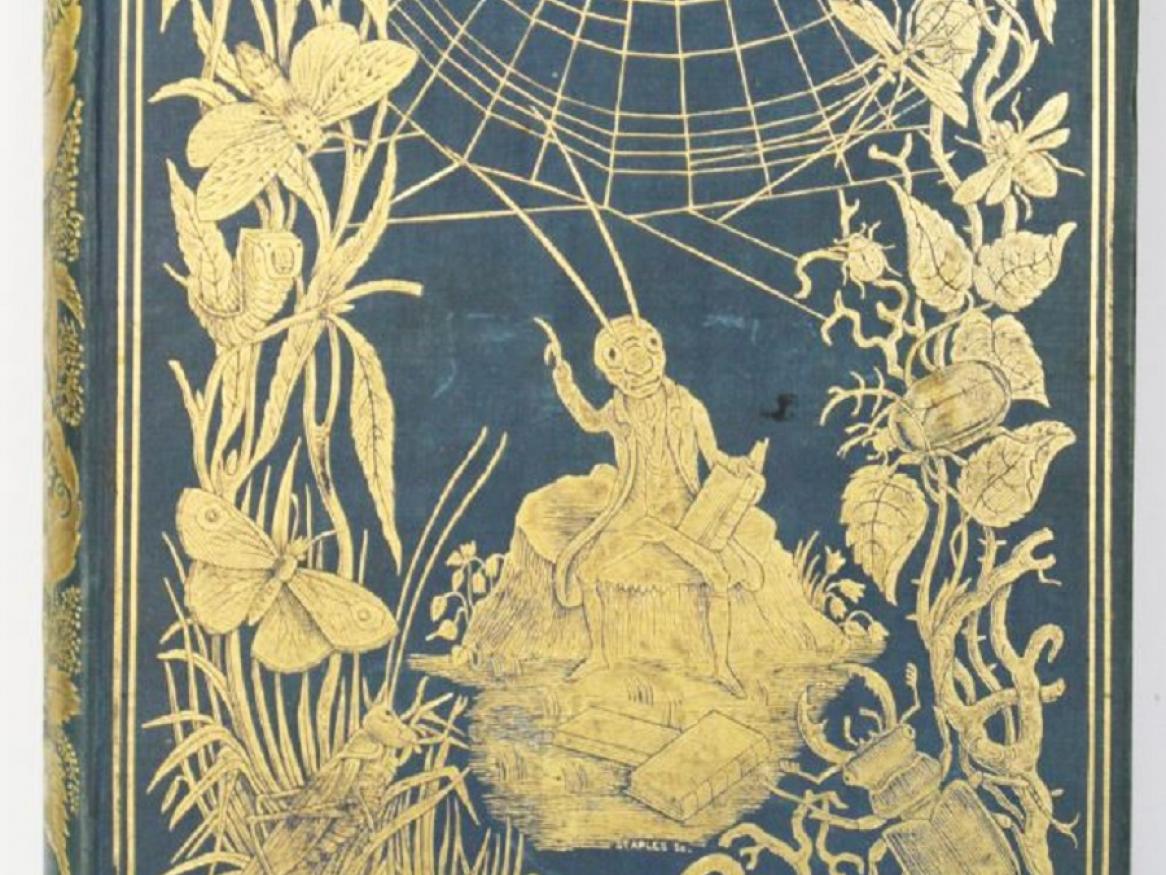

Formally established in 1957, the University’s rare books collections are among the oldest and largest in Australia. Encompassing some 100,000 volumes across 40 distinct collections, it contains volumes dating back to the 15th century, fine bindings, limited and private press editions, and many unique items.

Subject coverage is broad, with particular strengths in South Australian and Indigenous Australian history and culture; Pacific history; 19th century British and Australian literature; anatomy and medicine; science and natural history, and voyages and discovery.

Also included are publications of the University staff and official publications of its administration, academic departments and student societies and associations.

Items acquired for the rare book collections are selected for their enduring intellectual and historical value. They support current and future teaching and research, and are available on request to staff, students and the public.

Search Rare Books and Manuscripts collections

Rare Book Collection

The principal collection of over 40,000 books includes works published before 1840 (1900 for Australian works), fine and limited editions, works vulnerable because of their size or format, and selected publications of anticipated long-term research and reference value.

Strong Room Collection

The Strong Room Collection holds the University of Adelaide Library’s oldest and rarest books, majority of which were published before 1700. The collection also contains books which are highly significant to University and South Australian history, as well as rare and unique titles.

Minor Collections

Rare Books & Manuscripts also holds a number of minor collections which have been kept together because of their provenance, research inte

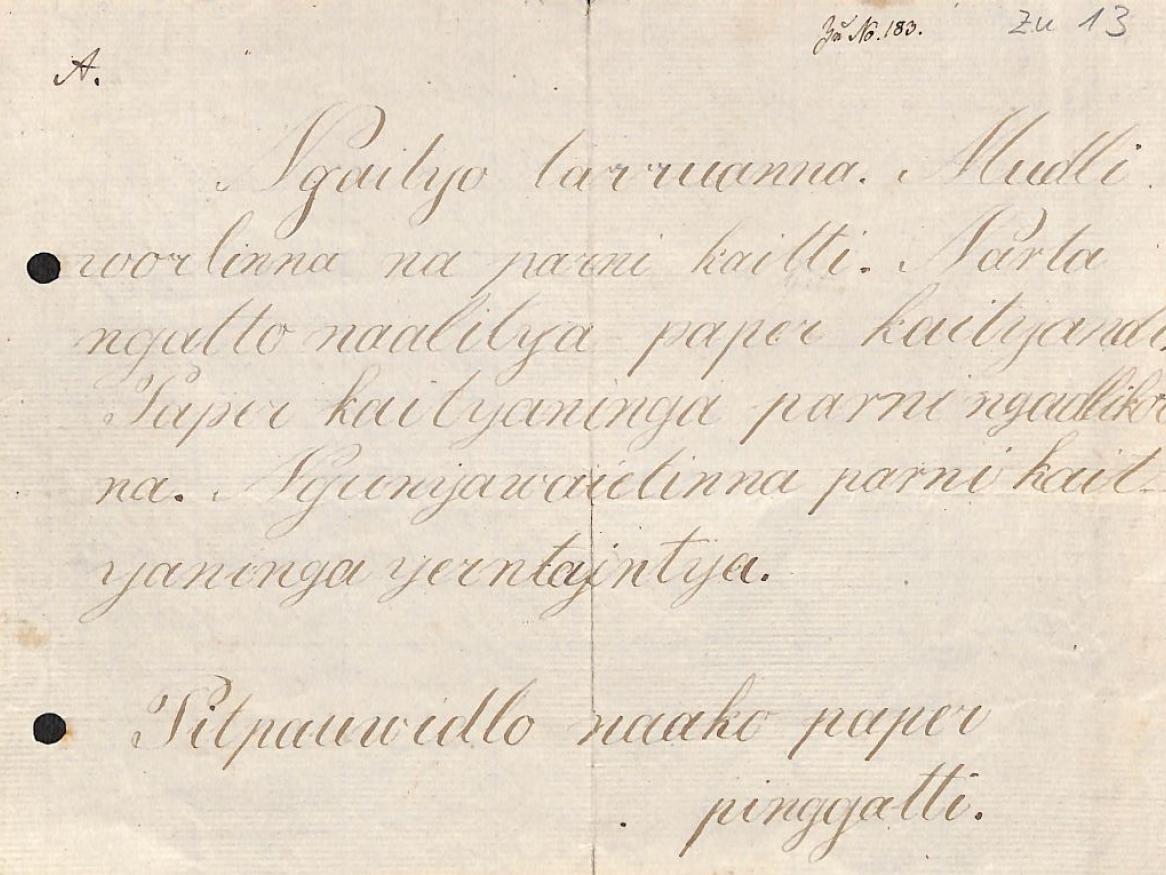

Pacific Collection

This expanding collection includes both books and journals on the history, culture, art, fiction and language of the Pacific islands of Melanesia, Micronesia and Polynesia, with particular emphasis on the central Pacific. Additional strengths include mission history and Pacific anthropology/ethnology journals.

University Collection

The University Collection is an archival collection of publications by past and present members of University of Adelaide staff, as well as those of the academic departments, University societies and associations, and student organisations. It also contains books, audio tapes and sound recordings created by or relating to members of the wider University of Adelaide community.

Theatre Collection

The Allan Wilkie - Frediswyde Hunter-Watts Theatre Collection comprises more than 6,000 books and journals and over 20,000 theatre programmes. It was bequeathed to the Barr Smith Library in 1976 by Miss Floy Angel Nan Symon and focuses principally on British and European theatre of the late 19th to mid-20th century.

Resources

The University Library's rare and unique collections are showcased through online and physical exhibitions, often in collaboration with a range of partners across the University and wider community.