Improving outcomes for young people transitioning to the workforce

Young peoples’ job prospects and mental health have been hit particularly hard by the coronavirus pandemic. With the momentous changes wrought by COVID-19, now is a good time to re-examine how we transition young people to the labour market.

Young people are suffering from lower employment and more stress

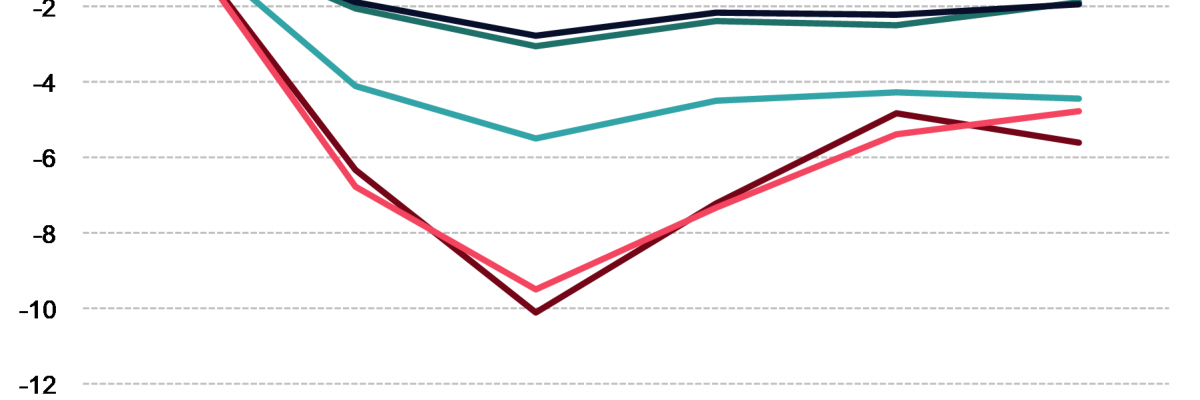

Young people have been hit particularly hard by the COVID-19 pandemic. ABS data indicates that employment rates fell most sharply for people aged 15 to 24 years and, to a lesser degree, 25 to 34 years in the immediate months of the lockdown and have been slower to recover – see figure below. A recent research note from the Melbourne Institute observes that these outcomes reflect that young people are more likely to work in casual jobs that offer less job protection, and in industries that have been most disrupted by the pandemic.

The Melbourne Institute also argues that young Australian also face higher rates of mental stress since in addition to the financial stress of unemployment or reduced hours, many young people live alone which can exacerbate stress through greater social isolation during a period of enforced social distancing.

In its recent Budget the Australian Government recognised the labour market plight of young Australians by introducing a wage subsidy for young people known as the JobMaker Hiring Credit. Under the scheme, eligible employers will be able to claim $200 per week for each additional eligible employee they hire aged 16 to 29 years, and $100 per week for each additional person aged 30 to 35 years.

However, the failure of the Australian Government to raise the base rate of the JobSeeker unemployment benefit, or to extend the existing $250 per fortnight Coronavirus Supplement which is due to expire at the end of this year, will disadvantage young Australians who are unable to find employment in the new year. SACES has previously argued that unemployment benefits need to be raised in order to reduce the poverty gap for unemployed people and provide them with better resourcing to find work.

Improving youth transitions to work

In addition to the challenges associated with trying to secure employment, the current economic crisis has greatly increased uncertainty regarding the economic outlook and has the potential to bring about significant structural change which will alter future patterns of employment. For example, some activities may not resume, while remote working will almost certainly be maintained at a level higher than before the pandemic. Given such uncertainty it is an opportune time to rethink how we best support young people make the transition from school to the labour force.

A recent paper by Dave Turner provides an excellent resource for thinking about how best to improve transitions out of education for young people. Drawing on academic literature and 30 years of international experience in youth employment, Dave shows that outcomes are maximised through a continuum of three important vocational learning elements comprising Work Exposure, Work Exploration and Work Experience. This continuum provides a ‘process of progression or scaffolding for young people to learn how to develop their work readiness and take greater leadership and responsibility for their own vocational learning, career development and their navigation of future employment pathways’.

The three elements of the continuum may be summarised as follows:

- Work exposure – activities that expose and illuminate young people to the unknown ‘world of work’ and career development.

- Work exploration – activities in which young people actively seek out information regarding career options, pathways, workplace norms and culture, including by interacting with people in the world of work. This process helps young people identify what might be of interest to them.

- Work experience – activities where young people are immersed in one or more workplace settings to develop a deeper appreciation for the workplace environment and gain practical experience. Such experience helps young people refine their interests and career preferences.

A notable feature of the continuum is that responsibility for driving the process shifts from educators to young people and employers.

The paper provides a guide and practical examples of how educators, employers and policy makers can provide the best opportunity for facilitating successful work outcomes for young people.