The Digital Dilemma: Countering Foreign Interference

SIP-02/2020

Key Summary:

|

|---|

Digitization of democratic processes in Australia induces new vulnerabilities that malign foreign entities can exploit to the detriment of our democratic sovereignty. Problems such as inauthenticity, data insecurity, and disinformation are amplified in today’s epoch of ‘digital era governance’.[1]

Australia’s digital-analogue hybridity is its core protection against foreign interference in processes such as elections and referenda. The State’s core weakness is the public sphere due to its open circulation of information which malign foreign entities can manipulate with disinformation. Australia is therefore relatively secure in terms of preference articulation, but vulnerable during phases of preference formation and agenda-setting. Although legislation designed to counter foreign interference has been enacted, current policy struggles to address the problem of disinformation or account for the covert nature of foreign interference. To ensure Australia remains resilient in the face of foreign interference we should: retain the digital-analogue hybrid system, continue investing in electoral integrity bodies, and seek to inoculate society against disinformation.

The Problem of Foreign Interference in the Digital Era

As democracies around the world are digitizing participatory infrastructure,[2] malign foreign entities (MFEs) are increasingly exploiting these newfound opportunities to the detriment of democratic nations. While foreign interference in democratic processes is nothing new, digitization of governance amplifies problems such as inauthenticity, data insecurity, and disinformation. Not only has it become more efficient to interfere in processes such as elections with the advent of electronic voting platforms, email, and digital databases, but widespread interference targeted at manipulating voters’ preferences is easier than ever due to the rise and prevalence of social media and the 24-hour news cycle.[3]

Interference in the 2016 US presidential election forced the issue into the limelight as the Russian government orchestrated a sophisticated electronic assault on US democracy.[4] Exhibiting the hallmarks of information warfare, interference targeted the very fabric of US political culture. The US case signalled the extent to which such interference has the potential to significantly undermine democracy – it highlighted for the first time the extent to which digitization can engender systemic weakness in a global superpower and bastion of democracy. In 2020, the US election process is ostensibly once again under siege, signalling that this is not a problem that will abate in the foreseeable future.

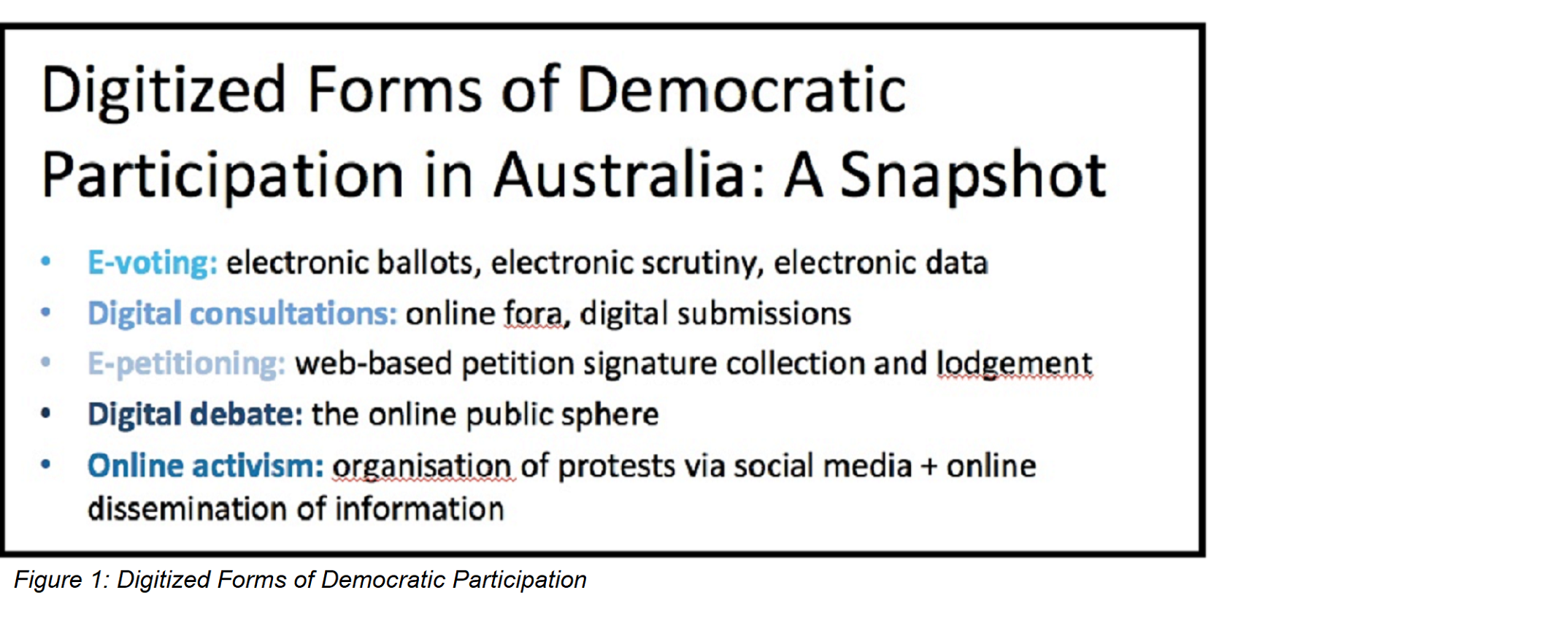

While Australia has yet to experience foreign interference at the same scale as the US or the UK, it remains at risk and countering foreign interference has become a strategic priority for the Australian government.[5] Incidents such as the 2019 parliamentary network hacking and foreign financing of political parties demonstrate that Australia is not immune to the foreign interference problem.[6] Following the global trend, Australia’s democracy is digitizing (see Figure 1) which presents new vulnerabilities to our democratic processes and institutions and new opportunities for MFEs to subvert the democratic foundations of our society.

Vulnerabilities in Australia’s Democratic Processes

MFEs can target Australia’s democratic processes to:

- Influence a policy output or election outcome; and/or

- Diminish social cohesion

Phishing for Outcomes

Since MFEs may aim to engineer a particular policy or electoral outcome, understanding the points of vulnerability in the decision-making process is crucial in order to prevent MFEs from succeeding in this regard.

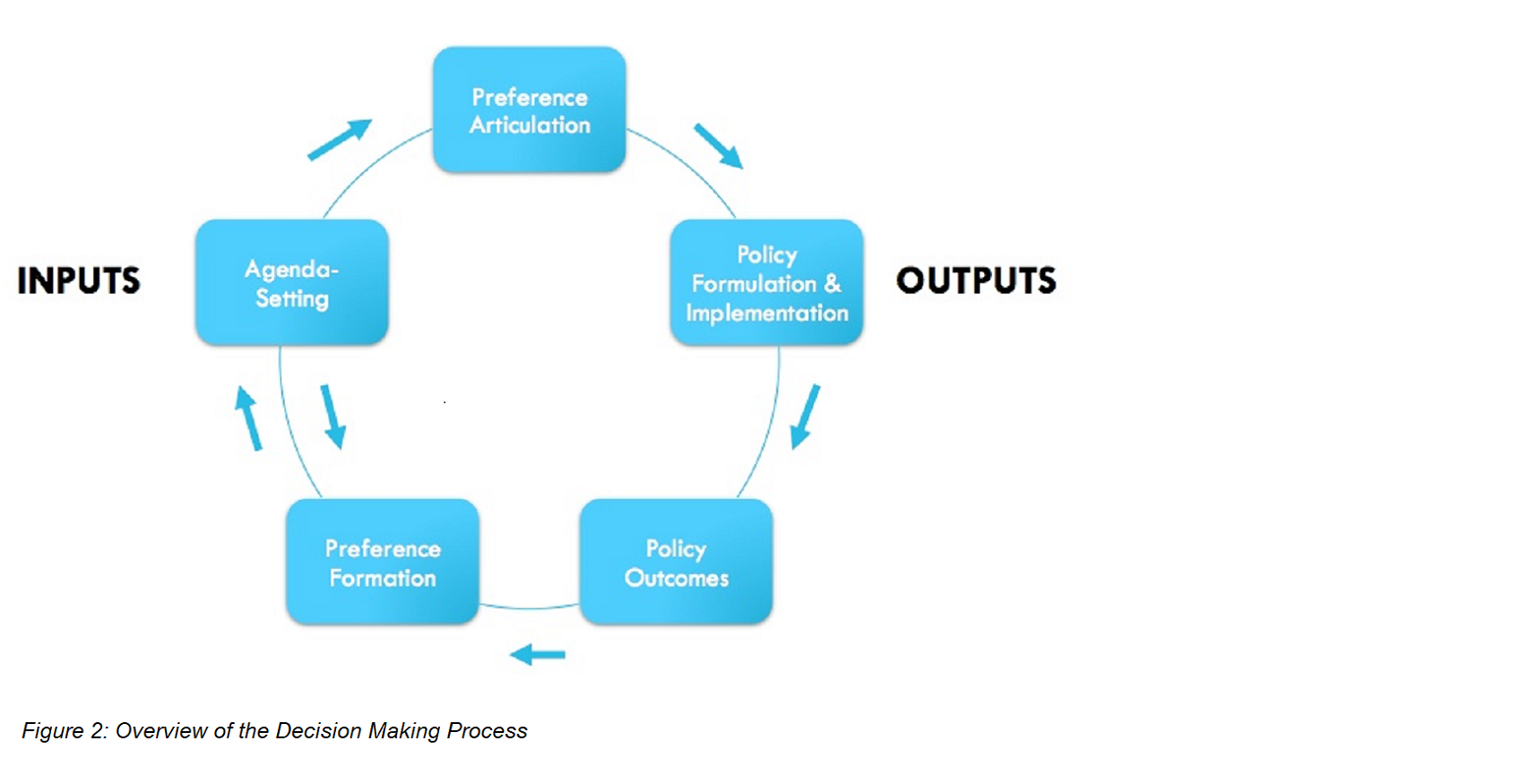

There are two overarching components to decision-making that are particularly relevant for the foreign interference problem: inputs and outputs. Inputs refer to phases of the process within which the public engages in discourse to bring attention to an issue (agenda-setting), along with the stage in which individuals form policy or candidate preferences (preference formation).[7] Preference articulation is the point at which one might, for example, vote, sign a petition, or contribute to a virtual departmental forum thus communicating preferences to government. Inputs contribute towards a policy or electoral output, in turn generating an outcome.

If MFEs are able to influence the inputs through manipulation of Australia’s mechanisms of public participation in politics, they gain power relative to domestic actors and can diminish national sovereignty and/or reduce the perceived legitimacy of participatory processes and institutions.

Fortunately, directly influencing an output in Australia is difficult due to stringent hybrid digital-analogue mechanisms which safeguard processes such as voting, departmental consultations, and petitions from the digital problems of inauthenticity and data (in)security.

Where digitization presents potential risks, analogue processes mitigate those risks. For example, although electronic mechanisms are becoming increasingly incorporated into the Australian electoral system and might introduce risks associated with data security, voting in federal elections and referenda is still characterized by predominantly analogue processes.[8] Paper-based voting systems render significant digital interference difficult:[9] the inauthenticity problem is diminished through onsite manual identity verification, and the data security problem is alleviated (though not entirely removed) by the possibility of cross-checking and auditing data with manual ballots and records.[10]

Despite the protections built into Australia’s democratic processes, the legitimacy of policy outputs can be undermined if there is public perception of a compromised input process - irrespective of whether interference has actually occurred.

The public sphere is therefore vulnerable since it is within the discursive space that information is circulated. It is also the area in which existing foreign interference policy is struggling to regulate, partly because robust regulation of the public sphere contravenes the tenets of democracy; a reminder of democracy’s fundamental weakness in information warfare.[11]

Hacking Minds[12]

Influencing policy outputs through disinformation is therefore a serious concern because it can reshape organic public inputs into the decision-making process. This indicates that while the preference articulation phase of participatory processes is largely secure, the preference formation and agenda-setting phases are vulnerable to MFE interference and can indeterminably affect policy outputs.

Interference that targets people before they cast a ballot, sign a petition, or join a protest is very difficult to detect, let alone counter. It affects what people think they want, which in turn will affect what they contribute to the participatory process – their input will reflect their interests, and their interests might be influenced by MFEs’ disinformation campaigns. Indeed, this remains a divisive issue with respect to the UK’s Brexit referendum – to what extent did Russian disinformation affect the result?[13]

Meddling takes its Troll

However, MFEs’ goals are not confined to achieving a specific policy or election outcome. Disinformation also manifests as an acute concern for Australian democracy for its potential to diminish social cohesion. Forms of democratic participation create opportunities for polarising discourse that has the capacity to exacerbate tension within society. Take for example, the Marriage Equality Survey of 2017: its very structure presented the issue in a binary manner with a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ vote required and it generated considerable polarised debate in the public sphere.[14] MFEs can capitalise on existing and endemic polarisation to increase societal fissures and weaken pillars of liberal democracy such as tolerance, inclusion, equality, and trust.[15] We saw such dynamics in the US where Russian disinformation operations reportedly fuelled protest activity without an allegiance to a particular side.[16]

Current Policy and Regulation

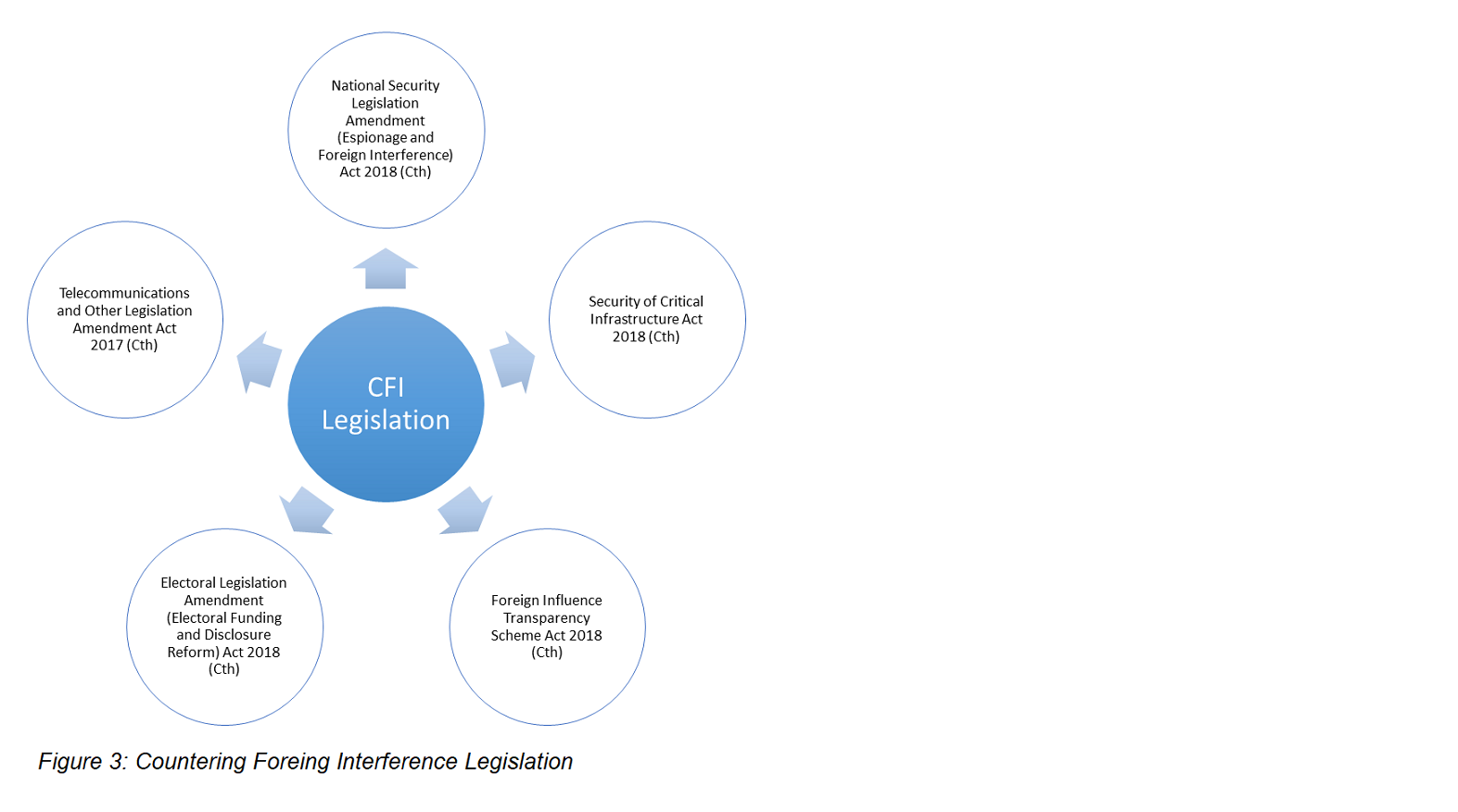

- Although Australia is developing a robust regulatory framework to protect democratic institutions from foreign interference (see figure 3), the extent to which legislative initiatives are effective is unknown and requires further investigation.

- Existing policy also struggles to address the deeper concern of disinformation targeted towards the public.

- By its very nature interference is covert and difficult to identify, meaning that the likelihood of legislation that criminalises foreign interference having either deterrent or punitive effects is questionable.

- Bodies such as the Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) and the Electoral Integrity Assurance Taskforce focus on maintaining electoral integrity, and ASIO’s Counter Foreign Interference Taskforce works towards mitigating foreign interference more broadly.

- The AEC contributes towards secure federal elections by overseeing and administering stringent voting procedures in line with the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 (Cth).

Policy Recommendations

- RESIST rolling out e-voting at the federal level. Since digital-analogue hybridity is a strength of Australia’s participatory processes we should continue to operate voting processes using a hybrid model.

- INVEST in bodies that promote the integrity of democratic processes and expand their purview to encompass the spectrum of participatory processes beyond voting since maintaining the integrity of democratic processes is paramount to countering foreign interference and building democratic resilience.

- INOCULATE society against disinformation. Since disinformation presents at the most acute concern we should educate regarding disinformation.

References

[1] Mark Evans et al., "Towards digital era governance: lessons from the Australian experience," in A Research Agenda for Public Administration (Edward Elgar Publishing, 2019).

[2] UN, United Nations E-Government Survey 2020: Digital Government in the Decade of Action for Sustainable Development, United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (2020),

[3] Michael L Miller and Cristian Vaccari, "Digital threats to democracy: comparative lessons and possible remedies," The International Journal of Press/Politics (2020).

[4] Elizabeth Anne Bodine-Baron et al., Countering Russian social media influence (RAND Corporation Santa Monica, 2018); Robert S Mueller, The Mueller report: Report on the investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 presidential election (WSBLD, 2019).

[5] "Countering Foreign Interference," 2020,

[6] Graeme Orr and Andrew Geddis, "Islands in the Storm? Responses to Foreign Electoral Interference in Australia and New Zealand," Election Law Journal: Rules, Politics, and Policy (2020).

[7] For policy-making processes see: Vivien A Schmidt, "Institutionalism," The Encyclopedia of Political Thought (2014); Thomas A Birkland, "Agenda setting in public policy," Handbook of public policy analysis: Theory, politics, and methods 125 (2007).

[8] Note that e-voting has been widely implemented in state elections and it has been trialled at the federal level. Aspects of federal elections aside from ballot casting have been digitized but are still subject to human oversight (e.g. 2016 election AEC scanning of Senate ballots using Fuji Xerox Document Management Services): see for example, "Electronic Voting at Federal Elections," Parliament of Australia 2016, accessed 8 September 2020; "iVote," 2020, accessed 12 August 2020; "iVote," 2020, accessed 12 August 2020.

[9] ISC, Russia Report (2020),.

[10] Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters, Second Interim Report on the Inquiry into the Conduct of the 2013 Federal Election: An assessment of electronic voting options, Parliament of Australia (2014); Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters, Report on the Conduct of the 2016 Federal Election and Matters Related Thereto, Parliament of Australia (2018),

[11] Laura Rosenberger and Lindsay Gorman, "How Democracies Can Win the Information Contest," The Washington Quarterly 43, no. 2 (2020).

[12] Henry Farrell and Bruce Schneier, "Common-knowledge attacks on democracy," Berkman Klein Center Research Publication, no. 2018-7 (2018).

[13] ISC, Russia Report.

[14] Australian Bureau of Statistics, Report on the Conduct of the Australian Marriage Law Postal Survey, ABS (2017).

[15] For features of democracy see: Robert A Dahl, On democracy (Yale university press, 2008).

[16] Mueller, The Mueller report: Report on the investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 presidential election; House Committee on Oversight and Reform, "National Security Subcommittee Seeks Classified Briefing on Foreign Interference in Racial Justice Protests," news release, June 16 2020, 2020,

About the Author: Melissa Dowling is a research fellow in the Department of Politics and International Relations at the University of Adelaide and is the lead researcher on the University’s Countering Foreign Interference defence project.

The views expressed here are the author’s, and may not necessarily represent the views of the Stretton Institute.

Feature image credit: Blue Coat Photos on Flickr

This work is licensed under Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.