Salt on the rise: What lagoon microbes reveal about the future of coastal ecosystems

Coastal lagoons are important biodiversity hotspots. Credit: Darcy Whittaker/@dwhittaker99_photo

When a coastal lagoon flips from crystal-clear waters to murky green soup, it’s not the fish that sound the alarm, it’s the microbes. These tiny organisms respond first to rising salt stress and nutrient pollution, acting as early indicators of ecosystem decline.

Environment Institute member Dr Christopher Keneally is leading research that puts microbial communities at the centre of lagoon health and restoration strategies. In a new global review, Dr Keneally and colleagues examined how climate change and human pressures are altering these systems, and what we can do to turn the tide.

Why coastal lagoons matter

Although they only make up about 13% of the world’s shoreline, coastal lagoons punch well above their weight in ecological and economic importance. These shallow, semi-enclosed bodies of water support global fisheries, buffer storm surges, and provide spaces for recreation. They also help filter nutrient runoff and store significant amounts of atmospheric carbon.

Sitting at the interface of rivers and oceans, coastal lagoons are highly sensitive ‘sentinel ecosystems.’ Changes in climate or land use upstream rapidly cascade through these systems, making them an early warning site for broader environmental shifts.

The importance of microbes

Microbes play a crucial role in keeping lagoon ecosystems in balance. They recycle nutrients, lock away carbon, and form the base of the food web. But when nutrient levels spike or salinity increases, that balance can tip and lead to toxic algal blooms, fish kills, and spikes in greenhouse gas emissions

In short: microbes are the first to respond and often determine whether a lagoon thrives or collapses.

What the research found

In his recent review, Dr Keneally investigated global studies on degraded lagoons to answer three key questions:

- How does rising salinity change microbial communities?

- What early warning signs can managers look for?

- What practical actions can reverse decline?

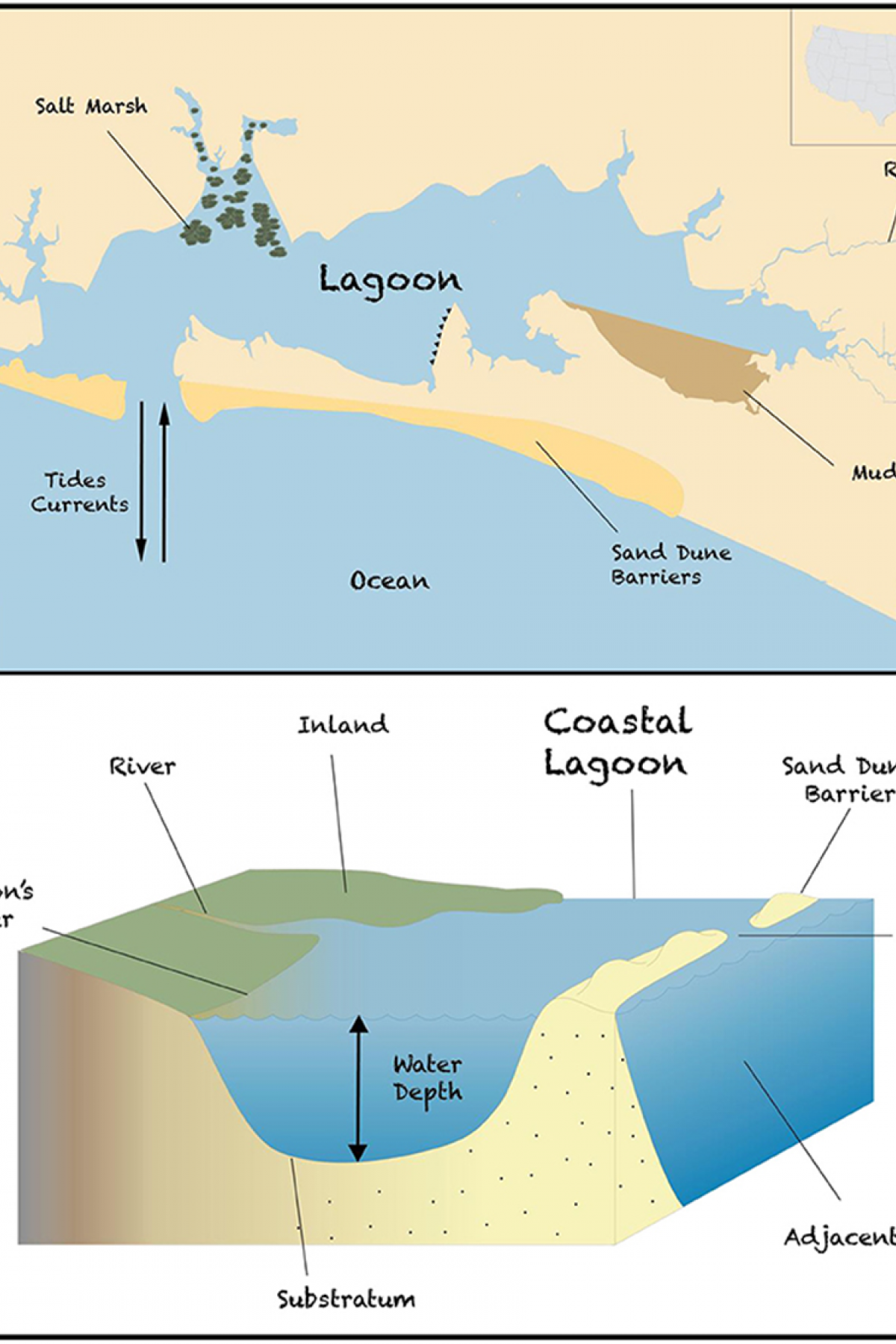

Coastal lagoon ecosystems are water bodies intermittently connected to the ocean. B) They are typically shallow and often concentrate nutrients and carbon from rivers and the sea.

Key findings include:

- Salinity tipping points: Once salt concentrations exceed ~40 grams per litre (compared to ~35 in seawater), microbial diversity and nutrient cycling processes begin to collapse, trapping nutrients in the system and driving algal blooms and greenhouse gas emissions.

- Microbial sentinels: A core group of salt-loving microbes can now be used to track lagoon health—offering managers a powerful early detection tool.

- Restoration levers: Interventions like targeted environmental water flows and better nutrient runoff control can slow or reverse degradation.

- Policy insights: This interdisciplinary review links microbiology, nutrient dynamics and greenhouse gas cycling—providing new direction for water quality standards and global carbon accounting.

Community and climate benefits

One standout example is the 2022 flooding event in South Australia's Coorong. The rapid reshuffling of microbial communities during high flows led to reduced nutrients and greenhouse gas production, showing how environmental water can be a powerful tool for both ecological and climate resilience.

By restoring degraded lagoons, we can turn these systems from carbon sources into carbon sinks, contributing to broader net-zero climate goals.

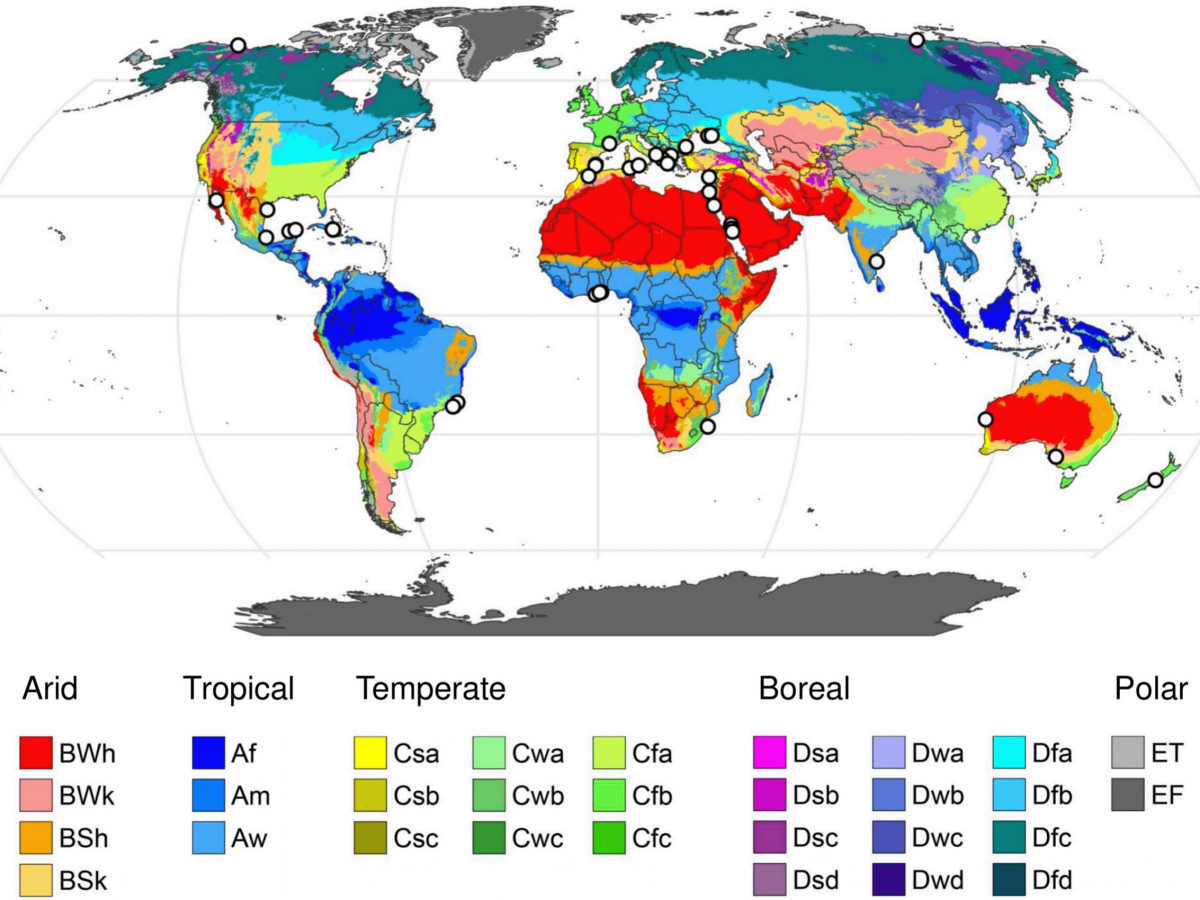

Global map of highly saline coastal lagoons, Background colours depict the Köppen-Geiger climate classification (https://www.gloh2o.org/koppen/).

Keneally et al. 2025 (Earth-Science Reviews)

What’s next?

- Developing real-time ecosystem models that integrate microbial responses with hydrology and climate data, giving managers a “what if” tool for flow releases and nutrient caps.

- Expanding research into understudied hypersaline lagoons, particularly in the Global South, to close data gaps and build a truly global understanding.

Coastal lagoons, and the microbes within, are some of the planet’s most sensitive indicators of change. These ecosystems may be small, but they offer big opportunities for protecting biodiversity, supporting livelihoods, and securing climate co-benefits.

Project Information

This project is part of the Department for Environment and Water's Healthy Coorong Healthy Basin Program, which is jointly funded by the Australian and South Australian Governments.

Partners and Researchers Involved

- Goyder Institute for Water Research

- Dr. Virginie Gaget (Adelaide Medical School)

- Dr. Daniel Chilton (Flinders University)

- Dr. Stephen Kidd (Biological Sciences, UofA)

- A/Prof. Luke Mosley (Ag. Food & Wine, UofA)

- A/Prof. David T. Welsh (Griffith University)

- Prof. Yongqiang Zhou & Dr. Lei Zhou (Chinese Academy of Sciences)

- Prof. Justin Brookes (Biological Sciences, UofA)

Further Information

Read the full article here (Earth-Science Reviews)

Recent article on 2022 floods in the Coorong (The Conversation)

Environment Institute ‘How freshwater transformed the Coorongs microbial world’

Newsletter & social media

Join us for a sensational mix of news, events and research at the Environment Institute. Find out about new initiatives and share with your friends what's happening.